They came from the mainland, crossing the treacherous waters of the channel in reed boats, carefully laden with their wares and livestock, the likes of which were wholly alien to the shores of the great island that lay before them. The narrow crossing was the penultimate stage in a journey that had taken countless generations and thousands of miles, from the Anatolian highlands at the fringes of the Near East all the way to the western edge of the continent in Ireland. By the time they had reached the shores of Brittany, they had become a seaworthy people, their route into Europe tracing the coast of the Mediterranean for millenia, slowly sowing the seeds of the continent with their new gods and language among the indigenous hunter gatherers, until finally meeting with another branch of Anatolian migrants who had made their passage up the Danube River. Here, facing the white cliffs of Dover, these two streams of travelers would combine their traditions with those of the nomadic hunters who had made the region their home since the end of the Ice Age. Here, the long vanished gods of a long vanquished people would be given offerings on the shores of the Atlantic, ancestors would be buried under great stone dolmens in a syncretism of the indigenous burial traditions of the hunters and new ways of the strangers from the east. And here, amassing like clusters of neurons against the synaptic barrier before bursting through the gap, these people would ford the crossing and forge the culture that would bring a new way of life to the British isles, a way of life immortalized in the greatest relics that today form their legacy, the iconic megaliths of Stonehenge, Avebury and countless others.

It could have happened this way. Or, perhaps not. The greatest advances of archeology, genetics, and linguistics can only peer so far into the abyss of time, and though we have learned much more about them in recent years, we fall prey to speculation and projection when we attempt to hone in on the lives of ancient peoples. Boats rot at the bottom of the sea, and languages and gods of people that left no written records can only be glimpsed in the fragments of their legacy that may have survived their conquest and woven themselves into the tongues and cultures that survive into the historical era. But if our curiosity is what compelled us to seek out distant seas and diverse landscapes, it is that which also compels us to understand our history, and the scientific method is only the most recent tool that we have in service of this pursuit.

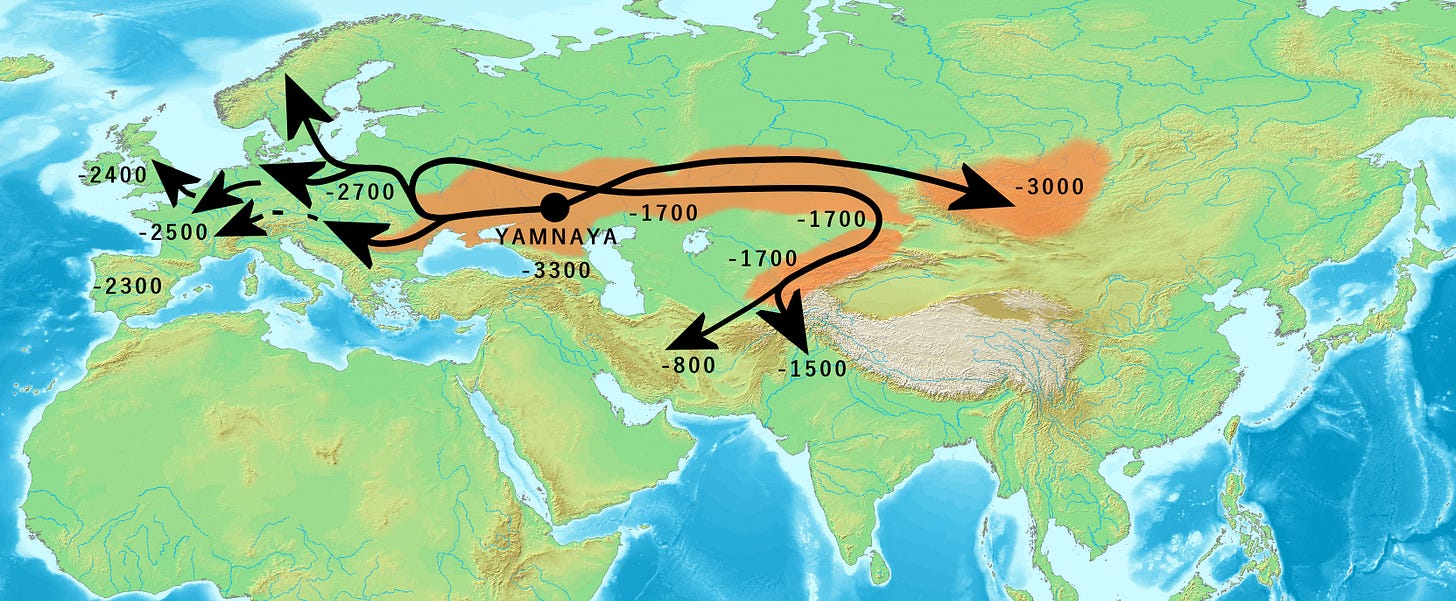

Lebor Gabála Érenn, or the Book of Invasions, is a Medieval Irish text that details the settlement of the island in prehistory. It tells of six distinct waves of migration that shaped the Irish people, beginning in 700 BCE. Among them were the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Milesians, the latter deposing the former when a powerful druid named Amergin summoned a great wave to ferry his people to shore despite a supernatural storm dispatched by the island’s inhabitants. The Tuatha Dé Danann surrendered to Amergin and his people, just as their predescessors the Fir Bolg had surrendered to them. As part of a bargain with the Milesians, they were banished to the Otherworld, the realm of faeries and gods in pagan Ireland, a place said to be reached by the numerous passage tombs and dolmens that rise from the land. The Milesians, who many believe represent the Gaelic people, were the last wave of settlers written of in the book. It is likely they who brought the Irish language to the island and it was their descendents who made the Tuatha Dé Danann their gods and kept the founding myth alive for many generations until it was cemented in writing. While most historians regard the text as apocryphal, it remains possible that it reflects a long standing oral tradition handed down for centuries, the details and chronology of which were tailored to fit into the Biblical view of the world proscribed by those who set these legends to paper. Just as Homer’s claims of the mythical city of Troy in the Iliad were only validated by modern archaeology, it is the bones of ancestral Europeans today that have reopened the debate about the veracity of legendary claims of ancient migrations. The last decade has brought about stunning advances in the field of ancient DNA research, and in 2014, a groundbreaking study1 proved that the ethnogenesis of modern Europeans resulted from three prehistoric waves of migration by Mesolithic(12,000-6,000 BCE) foragers, Neolithic (6,000-2,000 BCE) farmers, and Bronze Age(3,000-1,000 BCE) pastoralists. It would seem that the Irish bards were in the ballpark on the number of migrations, and just about right on the time frame, give or take 10,000 years.

The journey of our ancestors from their primordial homeland in Africa to their eventual dispersal to the farthest reaches of the world is nothing short of astonishing, a story so unbelievable that it is not just from adherence to dogma that many religious faiths find it difficult to swallow. But for those who endeavor to understand the mysteries that centuries of scientific research have uncovered, it is a tale every bit as miraculous and spellbinding as the origin stories of the Ojibwe, the Saami or the Irish.

From the Straights of Gibraltar2 that bridge the gap between Europe and Africa to the vast Siberian tundra that carried the first people towards the Beringian land bridge, the contemplation of the grandeur that awaited these pilgrims stokes the imagination and occupies a special place in our collective psyche. The religious scholar Mircae Eliade3 has suggested that ancient peoples likely viewed all of their activities as manifestations of the sacred act of the creation of the world, and this may have been true for the countless generations of hominins who ventured forth into the new continent, but it is important to remember that these same people had spent thousands of years honing their crafts and diversifying their languages in the equally primal and no less spectacular environs of Africa. We will never know what caused these migrants to cross the waters into a new land, but for all we know it may not have occurred to them that a threshold of any great consequence had been crossed at all. Perhaps a tribe of people felt the spark of divine providence and followed a charismatic leader across the waters with the promise that they too would be as gods in this new land. Or perhaps they were doing what their ancestors before them and countless descendants later are still doing- fleeing drought, famine or persecution in the faint hope that the untrodden grass before them would cover their tracks and lead them to better fortunes.

Europe has been home to hominins going as far back as Homo Erectus, and there is evidence of Neanderthal occupation of Britain going at least as far back as the Emian Interstadial Period4 that preceded the last Ice Age, when the north was warm enough that hippos swam in the waters of the Thames. But by the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, with most of the British Isles still locked in glaciers a mile thick and the subalpine regions of France and Spain providing a refugia from the cold conditions, Europe was still a sparsely populated wilderness. The Neanderthals were long gone, and soon the changing climate and melting glaciers would mark the end of the mammoth hunting tribes that had persisted there for millenia. The Aurignacian and Magdelanian cultures who hunted big game would be remembered for their incredible cave art on the walls of Chauvet and Lascaux, respectively, but they would leave little trace of their bloodlines in the DNA of modern Europeans. The people who would replace them likely migrated from the southeast, and practiced a way of life predicated on fishing, foraging and small game hunting, a Mesolithic economy reflected in the design of their microlithic spear and arrow points, a departure from the larger blades of their predecessors. These people, known to archeologists as Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG), ranged from the Balkans to the British Isles, which were at this time still connected to the mainland by a land bridge known as Doggerland that now lies submerged beneath the waves of the North Sea. During this time the Thames and the Rhine both shared the same watershed, the rivers and coasts teamed with Atlantic salmon and waterfowl, and the forests and grasslands were thick with red deer and aurochs. The cultivation and production of hazelnuts was a vital part of their economy, the harvesting and processing of which could have also functioned as a gathering point for disparate tribes to trade goods and arrange marriages. Strange headdresses made from deer antlers provide evidence of a shamanic religion, and large deposits of shell middens on the coast were covered with great slabs of stone under which bodies were covered with ochre and interred. The genetic evidence would suggest that these people likely had much darker skin than contemporary Europeans, and that they were mostly blue eyed, a controversial finding that shocked many laypeople. So rare is this phenotype today, and so radically different was the economy and ecology of that distant world, that it paints a vivid picture of what geneticist David Reich refers to as “the lost landscape of human variation.”

But the world was changing rapidly as it slowly emerged from the ice, and the land would undergo a change no less radical than that of her people before it would take the form that we know today. Sometime around 8,000 years ago, a massive glacial fissure off the coast of Norway unleashed a tsunami that would bury what little landmass of Doggerland had not already been consumed by the rising tides of the North Sea. This dramatic restructuring of the landscape would be a harbinger of another massive upheaval that was already making waves in the Mediterranean and making its way up the Danube corridor: the arrival of a strange new people and a way of life that would change the face of Europe.

The transition from foraging to farming among human societies is undoubtedly one of the most pivotal developments in the history of our species, and it is clear that this innovation evolved independently in several locations, disparate from one another by thousands of miles and in some cases thousands of years. But it is generally accepted that it happened first on the plains of the Levant, by a people known to us as the Natufian culture, over a few millenia following the period of rising temperatures and increased rainfall after the last Ice Age. This development has often been characterized as a Faustian bargain, one that allowed for a substantial increase in human population but which exacted a punishing toll in the form of grueling labor and an increase in malnutrition and disease. As settlements grew in size, the competition for arable land increased with it, and soon the nascent revolution would radiate from its source in every direction. By the time the farmers had reached the Anatolian highlands, they were building towns that were starting to look strangely like proto-cities. The ruins of Çatalhöyük on the Konya plain of modern day Türkiye, uncovered in 1958, seem almost dreamlike in their archaic structure. There does not appear to be any type of public architecture, only an Escher-like maze of honeycombed mudbrick houses, with the tops of the buildings serving as a public thoroughfare and most of the homes accessed from ladders on the rooftops. Inside, the walls were plastered and painted with murals of hunting scenes, ominous vultures, and what some have speculated may be the first map and the first landscape painting. The role of the ubiquitous “Goddess Figurines” found in many of the dwellings has been hotly debated, their purpose has been cited as evidence of a matriarchal society or simply dismissed as a form of ancient pornography. They buried their dead under the floors of their homes, and often kept the skulls of their ancestors on display, plastered over and eerily decorated with human features outlined in ochre.

The Mesolithic foragers of the Danube region in what is now Serbia were probably among the first to encounter these immigrants who began their journey across the Bosphorus, slowly colonizing the Aegean with their strange customs and domesticated sheep, cattle and pigs. The Iron Gates region of the Danube provided a rich and stable fishing economy for the foragers, who were wealthy enough to put down roots at a place called Lepenski Vir, where stone idols of bizarre fish gods decorated homes built in a trapezoidal shape to mimic a sacred mountain on the north bank of the river. Sometime around the mid 6th millennium BCE, the skeletons of the locals begin to show genetic evidence of admixture from a distinct new population, with a recent origin in Anatolia. This gene flow apparently went in both directions, as settlements also appeared in the archaeological record that were materially linked to a novel farming economy that also showed admixture from WHG populations. The newcomers were likely fairer skinned, with dark hair and brown eyes, and since they brought domesticated animals with them they may have also brought pathogens to which the indigenous foragers had no immunity. Could this exchange have played out in a similar fashion to the tragic destruction Cortez brought to the indigenous kingdoms of Mesoamerica? At this early stage, there is not much evidence of mass violence between the two groups, but it is clear that the continued progress of the farmers exerted pressure on the foragers, forcing them towards the coast and areas that were not suited to farming.

While one group of farmers made their way into central Europe, navigating the inland waterways, another group with whom they shared Anatolian ancestry took the coastal route along the Mediterranean, until both groups eventually converged around the Paris Basin in the 5th millennium. Both groups are known by their distinct pottery styles, the former as the Linear Band Ceramic (LBK) and the latter as the Cardial Ware culture. The LBK settlements brought with them a type of longhouse construction, incorporating burials under the floor of the house in a custom that probably originated in the Near East. On the other side of the continent, the Caridal Ware culture practiced similar traditions but seemed to be slowly incorporating more of the burial traditions of the Mesolithic foragers into their culture, who buried their dead under great slabs of stone and mounds of shells on the shores of the Atlantic.

Beginning on the shores of Brittany, monumental burial mounds and stone menhirs began to appear. This novel form of architecture was accompanied by an increase in grave goods, often in the form of jade axes imported from the Alps, suggesting extensive trade networks, social mobilization and the emergence of new forms of heirarchy.5 Genetic studies from the Paris Basin shortly before the emergence of the monuments does indicate admixture between the two streams of farmers, and to a lesser extent the Mesolithic foragers. The archaeologist Barry Cunliffe has proposed6 that this new burial tradition could be a reflection of a synthesis of the traditions of the farmers and the foragers, perhaps a harbinger of a new religion. And as their numbers began to swell, the lure of the distant island, sometimes visible through the mists of the channel, must have begun to pull their intrepid leaders under its sway.

This nameless and forgotten realm would soon encompass all of the British Isles. From Brittany to Normandy, ships were launched towards the last frontier of the Anatolian farmers, and from Wales to Ireland to the Orkney Archipelago the migrants sowed seeds of Emmer wheat and barley, their jade axes ringing out in the forests where the hunters had reigned since the retreat of the glaciers. By the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE, stone and timber circles and henges had replaced the causewayed enclosures and passage tombs of their forefathers, sometimes sprouting from the earth in the same places that had been sacred to the Mesolithic foragers whom they replaced. It was at this time that the main phase of Stonehenge was constructed. Over the course of the 3rd millenium, the builders of the world’s most famous megalithic circle moved immense boulders from as far away as Wales to be joined with locally quarried Sarsen stones, aligning the stones with the solstice and aligning the joints of the pillars with horizontal capstones in a way that has no parallel in the work of their contemporaries. But this shift in architecture may too have heralded a new religious awakening, perhaps rooted in a sense of desperation, like the Ghost Dance of the Plains Indians in America thousands of years later. The climate grew colder, the poplultion dwindled as the old farming systems were largely replaced by pastoralism, and a new wave was rising on the English Channel, this time in the form of riders from the Eurasion steppe.

The nomadic pastoralists who rode in from the endless grasslands of what is now Ukraine and Russia gained momentum as they swept across the Pannonian plain, taking brides among the farmers there but eliminating almost all of the male lineages from the genetic record. This hybrid group is known to archeologists as the Corded Ware culture, from the woven impressions on their pots, but thanks to recent genetic evidence, they are now known to be an offshoot of the Yamnaya culture of the Eurasion steppe who almost certainly brought the Indo-European languages to the continent,7 and who were probably among the first people to domesticate the horse. By the time they reached the British Isles, they had already absorbed or eliminated much of what remained of the Anatolian farmers, creating another hybrid culture known as the Bell Beakers, for their cermemonial drinking cups. By the end of the 3rd millenium BCE, the graves around Stonehenge begin to show evidence of novel burial rites and of great cheiftans interred with stone wristguards and bronze daggers and jewelry. And whether by disease, warfare or marginalization, the available genetic evidence from the period shows an almost total replacement of the farming lineages8 that had persisted in Britain since their arrival a thousand years before.

It is not known what language the Anatolian farmers spoke. Given their ultimate origin in the Near East, and the possibility of a scattering of ancient loanwords in Celtic and other Indo-European tongues, it has been speculated that they may have spoken a language distantly related to the Semitic family. Today, the only language in Europe9that may predate the steppe migrations is that of the Basque people in Spain and southern France, who speak a language of unknown pedigree and antiquity. Could the Basque tongue be a living relic of that ancient time whose only earthly witness is the massive stones interred in the soil over the brief period of their reign? The lineage of the Indo-Europeans persisted through the Bronze Age and into the historic era, so it is their gods and languages who remained for the first Greek and Roman historians to write about. But like the Tuatha Dé Danann, the forgotten farmers and the foragers who came before them linger at the edge of our consciousness like glimpses of a half remembered dream. They live on in our myths, in the margins of our languages and our genes, and in the sacred monuments that still serve as gateways to the distant past, the Otherworld of forgotten gods.

On a recent trip to the UK, I had the chance to visit Avebury, a remarkable megalithic site on the chalk downs just up the road from Stonehenge. Avebury is roughly contemporary with its more famous neighbor, built over a few centuries in the mid 3rd millennium BCE. It forms a sprawling complex of ancient long barrows, causewayed enclosures and great avenues, and what remains of the largest megalithic stone circle in the world. Today, many of the stones are gone, and the circle itself is interrupted by a quaint Medieval village that was plopped down in the middle of it in the Early Modern Period. There are gift shops, museums and throngs of visitors from all over the world, some dressed as fairies and sorcerers cosplaying amongst the stones as neopagan revelers dance and drum. As I wandered among the stones that had stood for 5,000 years and marveled at the construction of the enormous ditch that rings the circle, I found this intrusion of modernism and manufactured nostalgia to be slightly irritating. I kept trying to find opportunities to get a picture of the stones that would evoke their timeless power, and no sooner had I accomplished this than a woman in fairy wings or a family or five would stroll right into the shot, ruining the effect and increasing my annoyance. Within a few minutes of careful strategic brooding, I realized how ridiculous my irritation was. These monuments were meant to be experienced collectively. We will never know what motivated the Neolithic builders of Avebury to move thousands of tons of earth, with nothing more than antler picks and ox shoulder shovels, and to move the great pillars of Sarsen from their quarries to where they have stood now for millennia. We may never know for sure if this was some great communal feat of civic engineering and social cohesion or the frenzied labor of slaves coerced by some deranged warlord under pain of death. But when we look at the remarkable continuity of design and purpose of these monuments, from their nascent beginnings on the shores of Brittany to the tip of Scotland, it is clear they represent something of incredible collective significance. For a people who journeyed thousands of miles across a strange and forbidding wilderness, in a time when the tribe was one’s only bulwark against the forces of starvation and strife, joining these stones to the earth was a signpost, a powerful expression of tribal and religious identity. We stand now thousands of years from where they stood in time and light years removed culturally from the mores and values that shaped those voyagers and in turn shaped the land they colonized. And yet, their work remains, and standing in the ring of stones, with people of all walks of life from all corners of the globe, the faint echo of their voices can be heard, calling over time to us, perhaps asking us what we are building that will last another 5,000 years.

Identity is a powerful concept. History is rife with tyrants and conquerors using the forgotten “us” of the deep past to mobilize their people against a demonized “them” in the present. No one who pays any attention to the headlines needs to be reminded of how easily this type of thinking lends itself to atrocity. Who knows how far back we would need to travel to find a time when such tragedies did not persist among our species in some form? Such a time and place there likely never was. But that does not mean we should turn our backs on our history, and deny ourselves the wisdom of its traditions. Just like the first farmers in the Levant thousands of years ago, we have crossed a Rubicon where we may be potentially outflanked by the fruits of our experiements. The planet is warming again, the sea closing in much like it did for the ancient hunters of Doggerland. The world is changing all around us. If the future seems uncertain, the study of our history at least affords us with a periscope to peer through the murky waters of the past, where we can take some comfort in the hazy picture of our ancestors, gazing up at the same distant stars as us, struggling to navigate the rising tides and wondering what will become of their legacy.

To tell their story, shrouded though it may be in myth and projection, is to honor that legacy. To trace their footsteps is to walk in the dreamtime of the ancient world and to find our shared identity in the well of memory. And in the struggles and triumphs of their time, we may find some kinship with those of our own.

It is likely that homo sapiens reached Eurasia through the Arabian peninsula, but archaic humans may have crossed the Straight of Gibraltar

Eliade, Mircae The Sacred and the Profane

Wragg Sykes, Rebecca. Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art

Shennan, Stephen. The First Farmers of Europe: An Evolutionary Perspective

Cunliffe, Barry Bretons and Britons: The Fight for Identity

Reich, David. Who We Are and How We Got Here

In addition to Basque, the Uralic languages of Hungary, Finland and the Baltic states are not Indo-European, but these languages arrived in Europe after the Bronze Age

I love this sort of thing. I look forward to reading through your corpus.