There’s a woman that I think of from time to time. She is beautiful, despite the trouble in her mind that haunts her features. Her hands are rough and her eyes are wild, her gaze fixed on the horizon. The world around her is changing fast. Each night she lies under the constellations and worries about how she will find enough food for her children when the sun rises again. She lives at the mercy of the elements and her leaders in a place that has been plagued by war for most of human reckoning. It has gone by many names. Canaan's Land. Palestine. Israel. But the woman who walks the wilds of my imagination belongs to a people thousands of years older than any of those whose names come down through history. They are known to us as the Natufians, and they lived at the temporal margin of the Holocene, in the liminal twilight between the time of the forager and the time of the farmer, between the nomadic ways and those of their sedentary descendants who would one day raise the walls of Jericho.

Her people have lived off of this land for generations, stalking mountain gazelles and harvesting the wild plants of a region that was a thriving woodland in her ancestors' time. Far beyond the borders of her realm, the world-devouring glaciers are on the move again, for the brief interregnum between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Younger Dryas is coming to a close, and though her people know nothing of the encroaching ice the drought that they have wrought is hardship enough. Already the wild rye and lentils are going scarce, the gazelles fewer in number and the nagging hunger in her belly a portent of strife to come. But she is a dreamer, the heir to a lineage of wise women who have watched and listened to the plants as they drop their seeds to the earth.

You see this one? Her grandmother’s voice is clear in her mind as she gathers the dried seeds from the ground.

These are different. They do not shatter as they fall from their mother’s husk. Those are the ones to keep sacred.

No one believes that the spirit of the plant can be tamed by human hands. All the rituals of her people are done to curry favor with the wild, restless spirits of the hunt. It has always been this way. But as she gathers the seeds, carefully choosing the ones that her grandmother showed her, the ones that don’t shatter as they fall from the husk, she is weighing the gamble in her mind. To break with years of tradition is to risk incurring the wrath of the gods and the ire of the tribal elders. To do nothing is to risk starvation.

She breaks the dry earth with a flint blade, making a valley for the seeds that tumble from her hands. As she tills the rough soil, an earthworm slips through her fingers. She carries a bowl made from the skull of a small child, and within it a small reservoir of water from the creek near her camp. She douses the buried seeds and cuts a gash into her hand, rubbing her life force into the ground as if sealing the tomb of someone she dearly loved, and she pleads with the earth to carry them safely on their journey. The worm turns. She feels the stirrings of the soil, and she smiles. Her gift is well received.

We could call her Natufian Eve, a nod to those who think the Biblical fall from grace is an allegory for women’s role in the development of agriculture. Our Eve is a symbolic character, an amalgamation of a myriad of actors and a seminal process that can only be partially understood by archaeologists. But if I had to guess, I’m partial to the theory that agriculture may have initially developed out of “a glimmer in some hungry woman’s eye” as the late Barbara Ehrenreich mused in Blood Rites, her study of human warfare. If we operate under the hypothesis that Natufian men did the majority of the big game hunting, women would have likely filled the foraging niche, so it follows that they would have had the knowledge of plants necessary to become the first cultivators. If it is true that a woman was the first to unlock the secret of the grains that would forever shape the course of human history, she would have done so without any idea of the monuments, statecraft and glittering skyscrapers that would follow in the wake of her discovery. Like all true innovators, she had broken with tradition, and was likely met with little more than scorn and superstition for her efforts. To a hunter gatherer accustomed to living day to day from the bounty of the earth based entirely off one’s skill with a spear and knowledge of edible plants, the idea of investing time and labor into a project of delayed gratification may have been a hard sell for our young dissident. And even if the choice was made to sow seeds in the spring and return periodically within the confines of the hunting season, the switch to sedentary agriculture probably took thousands of years before it truly became a viable means of sustenance. She would have died without having any way of knowing where the wheel she had set in motion would wind up, and perhaps for all her efforts the forces of drought and starvation took her life and the lives of her children before she could derive any reward from her labor. The heart may be a lonely hunter, but for the dreamer it reaps a lonely harvest.

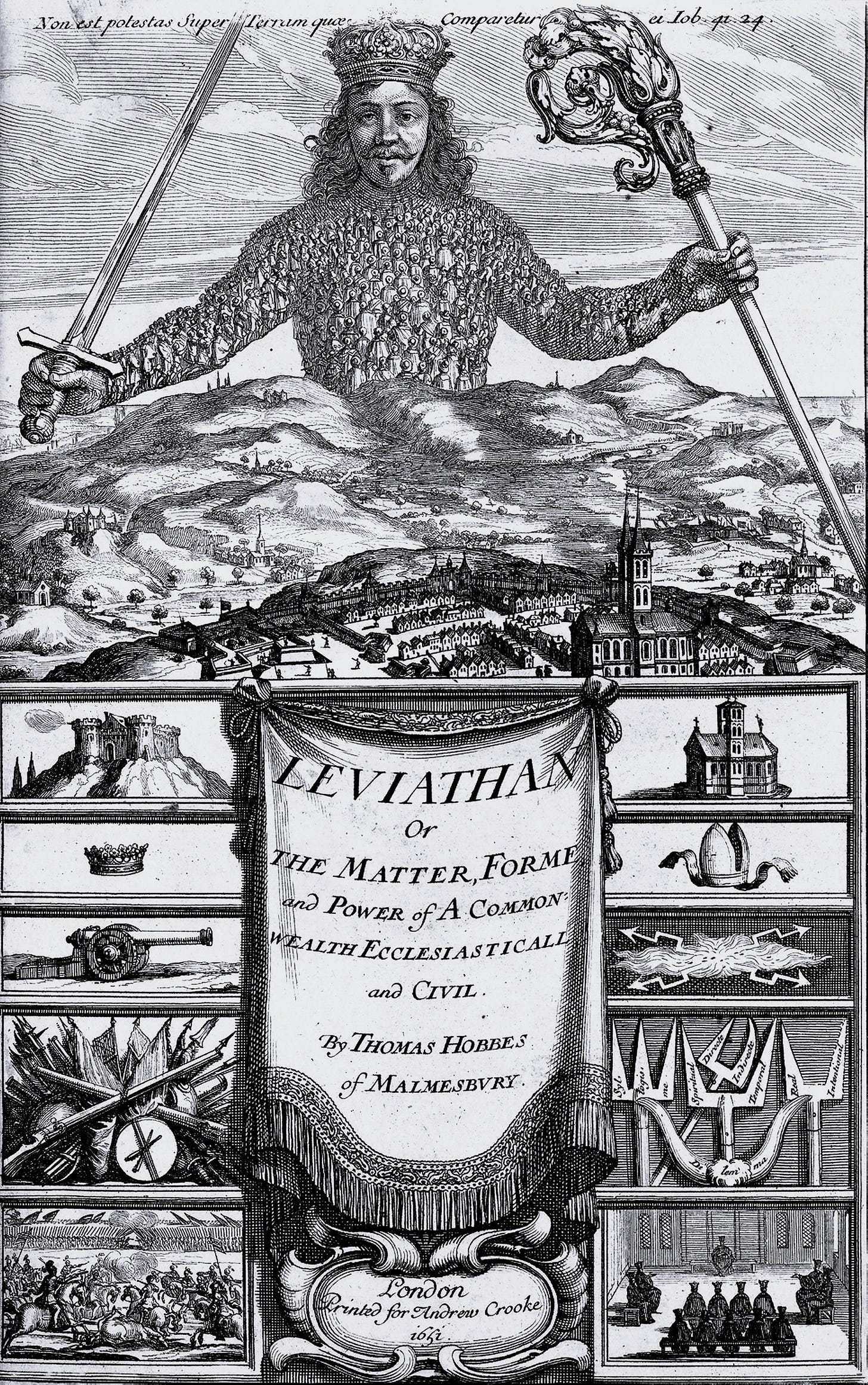

The first seeds may as well have been the first bricks in the walls of Jericho, then Çatalhöyük and Uruk, then Babylon and Rome. The entire edifice of civilization, the great Leviathan invoked by Thomas Hobbes, is built on the foundations laid by those nameless and forgotten cultivators. The spread of agriculture enabled numerous migrations and civilizations. From the first farmers to colonize Europe to the Bantu migrations in Africa, the demographic advantage inherent to farming would always prove devastating to the foragers these migrants displaced, often forming an unintended tandem with the pathogens that came with their domesticated animals as well. In the heat of the kilns that fired the pottery required to house the grain surplus of their yields they found the flame to temper blades of copper, bronze and steel. In turn these weapons would be used to fend off the marauders attracted by their grain and livestock. And in a society bound by the harsh calculus of Malthusian economics, the women of these settlements would have been vulnerable targets as well. In this way, the radical innovation of our female protagonist may have led not only to the development of organized warfare but to the perpetual subjugation of her half of the species as well. As the lonely harvest begins to bear fruit, it yields a bounty of regret as well.

Hobbes took his titular metaphor for the apparatus of the state from the Leviathan of the Bible, a great serpent descended from older Semetic and Mesopotamian myths. Perhaps the nascent worm made its first stirrings in the dry soil of the Levant, at the dawn of the Agricultural Revolution. It was a massive epochal shift for our species, but it was not the first, and it would not be the last. In our current era of exponential growth, it’s easy to forget that for hundreds of thousands of years the stone tool industries of our ancestors changed little. Around 50,000 years ago, the Cognitive Revolution arrived on the heels of the development of language and symbolic thought, witnessing the advent of sophisticated cave paintings and the demise of our only remaining hominid rivals, the Neanderthals. After the Last Glacial Maximum, the Agricultural Revolution would soon follow, but the speed of these developments pale in comparison to the onslaught of change that has come in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. In the span of a few centuries, the Leviathan that awakened when the first seeds were planted in the ground would grow to encompass the whole of the world with its tentacles of steel and concrete, filling the seas with its plastic entrails and choking the skies with the plumes of its great volcanic towers. We now live in a world of unmitigated innovation and growth. And as the landscape erupts with strange and novel structures, so too do the hearts and minds of her inhabitants mutate under the strain of these developments. Changes to mores and customs that once took centuries now can occur in a single generation. In this context, it is easy to understand why the charge “you don’t know your history” is so often levied against the young. The vessel of our progress moves at such great speed that the firmament vanishes rapidly beneath us, and as such the forgotten terrain becomes a fertile ground for the reactionary.

Like the conservative Natufian elders, the neo-reactionaries call themselves traditionalists. They occupy a slice of the broader global movement of a right wing ideology that has emerged in the last few decades. Although among them there is something of a heterodoxy of viewpoints the common refrain that emerges from their project is a rejection of modern progressive and woke ideologies and a return to traditional values, although exactly how far back and according to whose tradition is a matter of debate among them. They are an ancient breed. Once, they might say, humans could move no faster than the speed of the swiftest horse. Now we colonize the skies in machines that humble the gods, and so they raise their fists and shout at the clouds. Our pursuit of progress has corrupted us, leaving us blind to the dangers we have conjured into being. And perhaps on that point they are right.

For without tradition, we walk into a future of completely novel challenges and dangers. Much like our brave Natufian, the innovators of our time offer a vision of the future that is radically different from prior contexts of human evolution. Where the Industrial Revolution divorced us from the natural sleep cycles of day and night, the digital age has further married our minds and bodies to the strange dreaming of a hyperconnected global network that erodes our creativity and punctures holes in the social fabric that once was stitched together by the myths and traditions of our ancestors. Where the Agricultural Revolution entrenched the sexual division of labor that metastasized into the shackles of patriarchy, in the span of just a few generations the thousands of years of archetypes surrounding the male and female experience that have guided much of our cultural practices are rapidly dissolving, reflected in our language and our social mores. It is worth noting that there is substantial variation in the way traditional cultures across the world view gender roles, and there are many positive developments associated with shaking off some of the rigid hierarchies of the archetypes we have inherited in the western tradition. But the willingness to abandon the utility of gender entirely or embrace a transhumanist future where humans cede the authorship of their future to machines seems inherently risky, much in the same way that our ancestors could not possibly see how the impacts of their decision to plant a few seeds in the ground would lead to the innumerable catastrophes of the later Holocene.

And yet the scales of equality do seem to be heavily weighted in favor of change, and moved by the steady drumbeat of progress driven by the creative impulses of those who refuse to be shackled by the constraints of tradition. To abandon this drive entirely would have consigned our ancestors to the relative safety of the trees that graced the African savannah millenia ago. For better or worse, we will always be consumed by the Promethean fire that leads us into the future. And those who would seek to move us backwards often do not seem to spend much time contemplating how such a thing would even be possible. It has been said that the past is a foreign country, so it is perhaps a bit strange that a movement sometimes defined by its inhospitality to outsiders would want to transplant our society to a place where we cannot even speak the language. The desire to return to an idealized mythical past often works in tandem with disastrous forms of social engineering, and if the road to the future is blazed with unknown dangers, the road to the past is clearly marked with pitfalls well defined by the tragedies of the 20th century.

We have wandered far from the path out of the garden, and all roads seem to lead straight into the steel jaws of the Leviathan. The great migrations taken by the countless descendants of the first farmers are no longer available to the children of the earth, and so each generation becomes more closely tethered to the neural networks of the digital otherworld. Perhaps the darkest fear that is evoked by the conquest of the next frontier is that it will require us to relinquish much of what it means to really be human. Regardless of the scale of alarm that one feels is appropriate in the face of an approaching singularity, the erosion of human agency evokes an existential crisis that is hard for us to ignore.

And so it is that the rhetoric of our era draws once again from the well of apocolyptic imagery with which end times evangelists of all stripes shade their rantings. Tear down the walls of Jericho, God told the Israelites. Chant down Babylon, goes the defiant anthem of resistance. The Agricultural Revolution was the greatest mistake in the history of our species, says the famed historian Jared Diamond. From Bible bangers to Rastafarians to stuffy intellectuals, the fruits of the first farmers seem to make a powerful symbolic target for malcontents. In hindsight, creating a world devouring serpent probably was a bad idea. Perhaps progressives and traditionalists can agree on that much at least. We’re all stuck in the belly of the beast, and we don’t know where it’s going. If we were to do the famous time machine thought experiment all over again, maybe we’d agree to go all the way back to Natufian Eve and take her out instead of Hitler.

But I do feel for her. It’s lonely work, being a dreamer.

What a great read, man! Being someone who finds myself continually exhausted with political soldiers of either encampments (and in a lot of ways the encampments more generally), acutely skeptical of powerful institutions, but also deeply appreciative of the innumerable traditions we have carried with us for millennia, and for contemporary democracy (with it's many flaws), I find this speaks to me a lot haha

I really like the hand-cutting scene, using the blood to fertilize the nascent plants in the ground. Nicely done!